by Max Garcia, Sustainability Auburn Alumni Affiliate

I am a land use planner working and residing in St. Augustine, Florida that graduated from Auburn University in 2018 with a Bachelor of Science in Environmental Design.

I have fond memories of Tiger Transit on Auburn’s campus, especially when a car was not an option. As a recent graduate from 2018, I recall the Tiger Transit and Night Security Shuttle services were integral to the movement of many Auburn University students like myself. The digital infrastructure, reliability of service, the comfort within the shuttles, frequency and safety were collectively in sync to allow students to sleep in and responsibly plan their daily schedules. This system of transportation can be considered a “Bus Rapid Transit” (BRT) system, a transportation system utilizing a fleet of buses and stations along major corridors for efficient, local commuter transit. As students look forward, toward their career tracks, I’m curious how some students will move onto opportunities in communities with progressive transportation solutions. It is expected that if the transit system is generally safe, reliable, and efficient like Tiger Transit – the public too may advocate for implementing more advanced public transportation strategies beyond the car.

A popular concept related to improving transportation in the profession of land development and city planning is the concept of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD). “TOD” as a form of site development that supports especially compact commercial and residential development that supports a variety of transportation options and is aligned with a development pattern of transit stations along major streets and highways. Systems such as BRT, can support TOD entirely or is often worked into TOD networks to fill gaps from other available transportation options.

In the United States, recent dramatic legislative steps will motivate many cities to update their transportation systems. For example, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in 2021 guarantees $89.9 billion in funding specifically for public transit over the next five years. As populations continue to rise, students and the public alike, should expect their cities and government officials to seriously consider alternatives like Tiger Transit or commuter rail infrastructure to replace the single-occupant vehicle focus many of our communities are plagued with.

I will acknowledge that immense metro systems such as in New York City or Washington D.C. will not be suitable for many smaller cities, suburban communities, and rural environments that make up much of the country, including the Southeast. Scale and context are important to rationalize specific TOD strategies. However, cities in the Southeast, some much less than a day’s drive to Auburn’s campus, are beginning to acknowledge the potential of TOD in their future.

Brightline Transit Map and proposed expansion.

In recent news, there are at least three metropolitan areas utilizing or considering TOD as part of their strategic visions for transportation in the future: Southern Florida (Tampa – Miami), St. Johns County and Jacksonville, Florida, and Huntsville, Alabama.

In Southern Florida, the Brightline is an active metro rail that completed their first phase of construction in 2018. The Brightline serves the Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach Metropolitan Area and supports a metropolitan community of over 6 million people. Brightline includes three stations, with two more between Miami and West Palm Beach to be developed, expansion plans with multiple stations in Orlando and intends to finish the rail at Tampa on the West coast, about 400 miles total. By connecting three massive regions, the accessibility and mobility of the public in South Florida will have dramatic implications on the development of neighborhoods, whether economical or societal, around these stations.

Saint Augustine Transit Station Concept Plan.

In Northeast Florida, the oldest city in the United States, St. Augustine, recently considered an ordinance to create a new zoning and land use designation to specifically allow a transit-oriented station with a mixture of residential and commercial uses. Characteristics of the project include a maximum of 50 multi-family units per acre, commercial retail uses, a parking garage, and a transit hub that supports existing transit infrastructure such as local trolleys, buses, car-sharing, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure as shown in the concept plan. By comparison, in St. Johns County, where St. Augustine is located, the maximum density is 13-units per acre with minor increases permitted for affordable or workforce housing. St. Augustine itself has a maximum density of 16 units per acre, this ordinance is a dramatic proposal, but this TOD ordinance is also aligned with the Jacksonville Transit Authority’s recent unveiling of a commuter rail. In the next 10 years an existing railway will be converted to serve the public between St. Augustine and Central Jacksonville – a 40-mile journey with at least four stops: St. Augustine, FL, near a shopping mall, near a major commercial district, and finally central Jacksonville. This would allow the public to commute between these destinations, potentially removing thousands of daily travelers on Interstate 95 and other nearby major roadways.

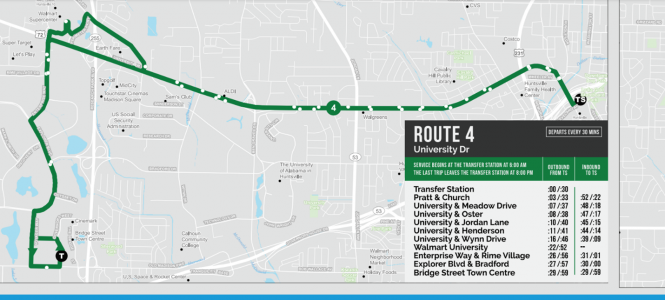

Route 4 will be the focus of BRT improvements, and later, a transit rail.

Finally, moving north to Huntsville, AL, the city’s transit authority has recently announced its own consideration of a light rail system in the city. However, it is decades away. The city is first vamping up their BRT system along University Drive, where the transit rail would even be considered. The city’s transit authority needs to prove to transportation agencies that such a route could even support ridership for a transit rail. That magic number is 3,000 daily users for Route 4 on University Drive, a route that is about 10 miles in length. If the ridership reflects favorably, the first proposed rail would connect downtown Huntsville to two mixed-use developments anchored by outdoor malls along a seven-mile stretch. The announcement motivated one friend of mine, a computer programmer for the military, a University of Huntsville graduate, and long-time resident of the area, to express to me, “this is what I’ve been waiting for, finally some decent infrastructure, traffic sucks on University Drive”. The implication of responsibly creating dramatic traffic solutions in this community, while smaller in comparison to the previous examples, is exciting none-the-less.

The prevalence of transit-oriented development is increasing in communities nearby Auburn, AL. As students at Auburn University continue to utilize systems like Tiger Transit, they may begin to acknowledge its impact on their ability to be successful in school, work, or personal life. The three regions discussed are communities with a diverse population that requires safe, reliable transportation to succeed in personal and professional goals. Much like Tiger Transit, I am excited by the prospect of TOD improving the wellbeing of the public and investing in its users.

Learn about the SDGs & AU and our contributions related to this post.