“In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.” Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

Aldo Leopold, a forester and ecologist, published a collection of essays in A Sand County Almanac in 1949. It is recognized as a classic work, a foundational text for the environmental movement of the 1960s. In it, he calls for a land ethic to guide humanity’s relationship with the natural world: “There is as yet no ethic dealing with man’s relationship to land and to the animals and plants which grow upon it…. The land relation is still strictly economic, entailing privileges but not obligations.”

What is a land ethic? From the Aldo Leopold Foundation: “In Leopold’s vision of a land ethic, the relationships between people and land are intertwined: care for people cannot be separated from care for the land. A land ethic is a moral code of conduct that grows out of these interconnected caring relationships.”

A Sand County Almanac came immediately to mind as I thought about commenting on international Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15, Life on Land: “Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.”

SDG 15 is one of 17 Sustainable Development Goals created by the nations of the world under the auspices of the United Nations. Given that this goal was created in 2015 to address one of the grand challenges of our time, the destruction of the terrestrial biosphere, it is obvious that Leopold’s call for an ethic 72 years ago has yet to be heeded.

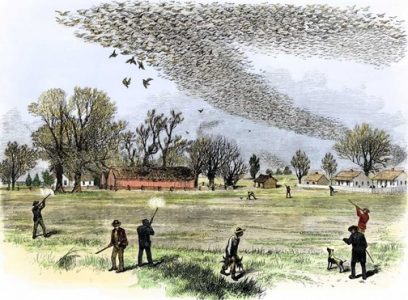

The artwork titled Shooting Wild Pigeons in Northern Louisiana is based on a sketch by Smith Bennett and appeared in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of July 3, 1875. Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News/Wikimedia Commons

Leopold lamented decades of wanton destruction of life in his little book: the death of the last passenger pigeon in 1899; an account in 1870 of two brothers who shot 210 blue-wing teal in one day; a hunter who in 1869 shot 6,000 ducks in one season; the destruction of every stand of majestic white pine in the Great Lakes region.

A lot of people have denounced the rapacious and careless slaughter of life and living systems. Theodore Roosevelt, early in the 20th century: “Here in the United States we turn our rivers and streams into sewers and dumping grounds; we pollute the air; we destroy forests; and we exterminate fishes, birds, and mammals….”

Fast forward to the 21st century, and we find humanity, merely 0.01 percent of the Earth’s biomass, causing the sixth mass extinction of species in geologic time. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2018 shows that humans and our livestock now comprise 96% of mammalian biomass on the planet. Humans account for about 36 percent of mammalian biomass. Domesticated livestock, mostly cows and pigs, account for 60 percent, and wild mammals only 4 percent. Since civilization began humans have wiped out 83 percent of wild mammals and 50 percent of plants, while domesticated livestock numbers have exploded.

A growing number of scientists argue that we have left the Holocene Epoch and entered the Anthropocene, a period where human beings have become the dominant force on the planet. Lacking a land ethic, a moral code of conduct, the dominant culture’s impact is increasingly disruptive and destructive to life on Earth.

As long as land is perceived as property to do with what we will for our own narrow and self-centered purposes, we are in trouble. As Leopold put it, “Land-use ethics are still governed wholly by economic self-interest, just as social ethics were a century ago.”

He writes: “All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts…. The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, water, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”

Through his ecologist lens, Leopold makes clear that, contrary to the predominant myth that humanity is above the natural world, we are indeed of the natural world, “plain members and citizens of it.” In fact, as members of the global community of living things, Homo sapiens as a species is a very recent addition. We are the new kids on the block.

All this begs the question: If a land ethic is so important, how do we go about cultivating it?

Leopold explains: “A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land.”

So to have a land ethic, we need an ecological conscience. What is that?

I like what lawyer and biochemist Joseph Guth wrote in the Vermont Journal of Environmental Law: “Nothing is more important to human beings than an ecologically functioning, life-sustaining biosphere on the Earth. It is the only habitable place we know of in a forbidding universe. We all depend on it to live, and we are compelled to share it; it is our only home… Many deep physical and psychological aspects of our human nature dovetail with the attributes of the Earth, often in ways that we perceive only dimly, if at all. The Earth’s biosphere seems almost magically suited to human beings, and indeed it is, for we evolved through eons of intimate immersion within it… We cannot live long or well without a functioning biosphere, and so it is worth everything we have.”

Okay then. So how do we cultivate an ecological conscience?

Wiser people than I say the answer is: Biophilia.

The term biophilia was first used by psychologist Erich Fromm, who explained biophilia as “the passionate love of life and of all that is alive.” E.O. Wilson, the Mobile-born and raised and Pulitzer Prize-winning biologist, wrote the book Biophilia (1984). In it he postulates that Homo sapiens have a genetically ingrained affinity for the natural world from which we emerged and in which we are “plain members and citizens.”

Just this week, research on biophilia was published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology. The study concludes: “The present findings provide clear evidence in support of biophilia theory….” (It does not address Wilson’s genetics claim.)

Given each one’s inherent connection to the natural world, all it takes to create an ecological conscience is awakening to this relationship and cultivating our sensitivity. Doing that, we can perceive beauty and richness of life all around us, an experiential awareness that inspires and enriches us in ways we cannot imagine.

Those individuals who nurture their in-born biophilia do so to amazing effect. I will name two examples.

One is Rachel Carson, the author of several important works, including Silent Spring, the seminal book from 1962 that was another catalyst for the modern environmental movement. Rachel grew up outside of Pittsburgh, immersed in nature. Twenty years before Silent Spring, she wrote the following after visiting Chesapeake Bay for the first time: “To stand at the edge of the sea, to sense the ebb and flow of the tides, to feel the breath of a mist moving over a great salt marsh, to watch the flight of shore birds that have swept up and down the surf lines of the continents for untold thousands of years, to see the running of the old eels and the young shad to the sea, is to have knowledge of things that are as nearly eternal as any earthly life can be.”

Only someone who loves life, someone who is receptive and connected enough to be deeply moved, can write something like that.

Another is the painter Henri Matisse. There is an enlightening story told by composer and conductor Andre Kostelanetz, who in 1945 visited Matisse at his home in the French Riviera town of Vence. Kostelanetz wrote: “The place was covered with paintings, most of them obviously new ones. I marveled at his production, and I asked him, ‘What is your inspiration?’

‘I grow artichokes,’ he said.”

Red Interior, Still Life on a Blue Table, 1947 by Henri Matisse

Kostelanetz goes on: “His eyes smiled at my surprise and he went on to explain: ‘Every morning I go into the garden and watch these plants. I see the play of light and shade on the leaves and I discover new combinations of colors and fantastic patterns. I study them. They inspire me. Then I go back into the studio and paint.’ ”

Kostelanetz: “This struck me forcefully. Here was perhaps the world’s most celebrated living painter. He was approaching eighty and I would have thought that he had seen every combination of light and shade imaginable. Yet every day he got fresh inspiration from the sunlight on an artichoke. It seemed to charge the delicate dynamo of his genius with an effervescent energy almost inexhaustible.”

That, my friends, is biophilia fully expressed.

The concepts behind the terms that Fromm, Wilson, and Leopold used – biophilia, ecological conscience, and land ethic – are ancient. Indigenous cultures in North America and elsewhere have lived them for thousands of years.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a professor of botany. As a Native Amerian and PhD-holding botanist she bridges the gap between Native and European science, wisdom, and culture. Her wonderful book Braiding Sweetgrass is, I think, a sacred and scientific reflection of these ancient values.

Regarding Europeans who invaded North America – already populated with millions of people living by a land ethic – she writes: “Had the new people learned what Original Man was taught at a council of animals – never damage Creation, and never interfere with the sacred purpose of another being – the eagle would look down on a different world. The salmon would be crowding up the rivers, and passenger pigeons would darken the sky. Wolves, cranes, Nehalem, cougars, Lenape, old-growth forests would still be here, each fulfilling their sacred purpose.”

Imagine being the eagle looking down on that world. It would certainly be more humane and whole.

There are pathways of sustainability available to us that would enable us to create a world more humane and whole; pathways that nurture our biophilia – which includes the love of all humanity; pathways that cultivate a sense of loving responsibility to the land and sea community of all living beings; pathways that call us to embrace a land ethic as our “moral code of conduct that grows out of these interconnected caring relationships.”

These pathways are more than romantic musings or idealistic dreams. They are the pathways of life.

Biophilia, an ecological conscience, and a land ethic are more than would-be-nice-to-have aspirations. They are rock-solid requisites for a living future. That is the case because they honor the nature of existence itself.

Not convinced? Ponder physicist Fritjof Capra’s comment on the nature of reality: “Ultimately, as quantum physics showed so dramatically, there are not parts at all. What we call a part is merely a pattern in an inseparable web of relationships.”

Learn about the SDGs & AU and Auburn’s contributions related to this post.