Whether we prefer to eat something sweet (imagine those blueberry pancakes dripping with maple syrup!) or savory (hear the crunch of a fresh juicy !); whether we like to drink a cup of steaming coffee or freshly pressed orange juice; our plates share one thing: Pollinators!

Figure 1: Honey bees filling wax cells with pollen collected from plants that may end up in the grocery store as fruit or vegetable.

At least one third of the food we eat relies on pollinators! These creatures move pollen from the male part of a plant to the female part. This results in ovule fertilization, production of seeds, and ovary tissue development.. Long story short – the ovary tissues are the part of the apple or pear that we eat!

But who are these pollinators?

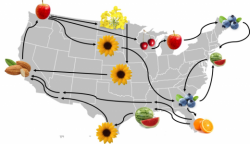

Figure 2: For simplicity, here are a few honey bee colony migratory routes.

There are the inconspicuous ones: bats, birds, butterflies, beetles and others. And then, there are the more obvious, well-known ones: Honey bees and native bees. Bees don’t just selflessly pollinate plants though. This ecosystem service is rather a by-product of bees collecting pollen for themselves to eat. Economically speaking, honey bees pollinate crops worth about $15 billion each year in the United States! To provide such extensive pollination services, beekeepers purposefully move their colonies across the country to pollinate different crops (Figure 2).

Estimating the monetary value of pollination provided by the ~ 4,000 species of native bees isn’t as easy. Unlike honey bees, most native bees are living solitarily in the wild without human management pollinating plants incognito (Figure 3). There are some exceptions. Bumble bees for example, can be native bees hired to pollinate tomatoes, and the solitary mason bees are often used in apple orchards.

Figure 3: Mining bee (genus Andrena) with pollen pants in an Auburn parking lot.

One thing honey bees and native bees share is that they face some serious problems. Last year alone, beekeepers lost about 40% of their colonies. It’s even worse for native bees. In 2017, an extensive review revealed that more than 50% of native bee species are in decline. Scientists agree that these declines cannot be explained by one single but rather an interaction of multiple factors. And climate change plays a notable role in this complex system of bee stressors. Here’s how:

Shifting temperatures. Overall, monthly average temperatures are increasing. One could argue that this is beneficial for some bees; honey bees for example rarely fly at temperatures below 50˚F (10˚C). On the flip side, shifting temperatures could also cause flowers to bloom earlier in the season and we don’t understand yet whether bees will follow suit (Figure 4). Generalist bees that forage on a variety of different plants may be able to cope with such mismatches, but especially affect specialist bees which forage exclusively on one plant. As an example: The Gulf coast solitary bee (Hesperapis oraria) only consumes pollen and nectar from the coastal plain honeycomb-head, which in return cannot reproduce without this particular bee.

Figure 4: February 2020 in Auburn, AL. Frozen ground around a beehive at the same time Dandelion is blooming. Are the bees ready to go out and forage on it?

Habitat loss. Some animals like butterflies have been able to expand their habitat further North while maintaining their Southern range limits due to warmer temperatures. Bumble bees don’t seem to follow the same pattern though. Not only do they NOT move further North, but their Southern habitats are actually shrinking rather than staying the same. One potential reason for the smaller Southern ranges is land-use change. In recent years, urban areas and agricultural landscapes have expanded. Along with this, intensified agricultural practices such as pesticide use further limit suitable habitat for pollinators.

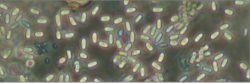

Figure 5: Microscopic picture of Nosema spp. found in a honey bee gut.

Pest and diseases. Due to the high densities and large-scale movements, honey bees are prone to disease outbreaks, invasions of pests and parasite infections. Nosema ceranae is a gut parasite of honey bees (Figure 5). Originally from Asia, this parasite has spread into other parts of the world (including the United States) due to global trades and has been associated with elevated colony losses. The good news is that colder temperatures help to reduce the prevalence of Nosema. The bad news is that with increasing temperatures, this parasite is predicted to become more prevalent and virulent strains will likely predominate in the future. This does not only concern honey bees though! Nosema can be transmitted to bumble bees when they forage on the same flowers as infected honey bees did.

In summary, climate change adds another layer to other environmental stressors that honey bees and native bees already face. Given that bees are critical to our food security, the U.S. economy and environmental health, something has to change…

To end on a positive note: Everybody can actually change something and support bees and pollinators on a small scale. Why not planting some wildflowers out in your garden (or in pots if you happen to live in an apartment)? Planting a variety of flowers that bloom at different times of the year will benefit all kinds of pollinators (Figure 6). There are plenty of resources providing lists of pollinator friendly flowers.

Even better: Why not plant your own vegetable and/or herb garden? Squash, tomatoes, rosemary, and lavender will attract a diverse group of pollinators and your dinner plate will look appealing to you.

Figure 6: Wildflowers for pollinators. Planting a variety of different flowers that bloom at different times will make pollinators and yourself happy all year long.

Post contributed by Selina Bruckner, Auburn University Bee Lab.