“Nature doesn’t have a design problem. People do.”

~William McDonough and Michael Braungart in Cradle to Cradle

Our mental models, store our internal assumptions about the way the world works, determine how we see and behave in the world. We accept unexamined assumptions as the way things are, the way things work. As physicist David Bohm put it: “[We practice] the almost universal habit of taking the content of our thought for a description of the world as it is.”

The problem is that the unexamined content of our thought can blind us. Our worldviews and perceptions can keep us locked in patterns of behavior that perpetuate the status quo and prevent us from perceiving new, clearer ways of thinking and acting that are more in line with the way the world actually works.

A good example of that is how we think about the concept of “waste.” Actually, we usually don’t think about it and that’s the point. We accept “waste” as a legitimate thing, a normal part of life, a consequence of doing stuff. We make stuff, there is waste. We use stuff, there is waste. We throw stuff away, it is waste.

When we do give thought to something other than throwing stuff away, like recycling or “waste diversion” by another name, we are reducing the waste stream somewhat and that’s a good thing. But it doesn’t call into question the very concept of waste.

Waste is a market failure. Waste is a design flaw. Waste is, well, waste.

In nature there is no such thing as “waste.” In nature waste equals food. Always. Even “waste” discharged by humans and other animals is food for other organisms. They break this material down into benign, usable nutrients. In nature a “waste” stream is really a nutrient stream.

What if we eliminated the concept of waste? It’s a task that needs to be on the human to-do list. The first system condition of a sustainable world is to live in accord with the laws of nature. That means rethinking waste so that the leftovers of our activities become food for another purpose. It becomes a nature-mimicking nutrient stream.

Bill McDonough and Michael Braungart are paradigm-shifting thought leaders in the sustainability movement. McDonough is an American architect and Braungart a German chemist. In 1992 they drafted the Hannover Principles, Design for Sustainability. This document was created for planning Expo 2000, a World’s Fair in Hannover, Germany in the year 2000.

There are nine Hannover Principles. Number six states: “Eliminate the concept of waste. Evaluate and optimize the full life-cycle of products and processes, to approach the state of natural systems, in which there is no waste.”

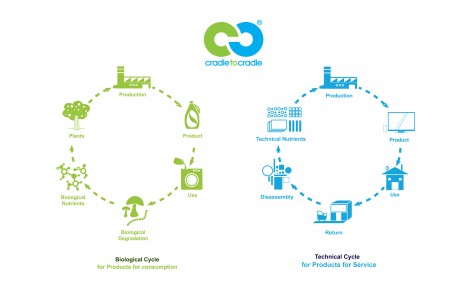

We can design things in ways to accomplish this. As McDonough puts it, the metabolism of the technosphere (the way we make, use, and dispose of stuff) can mimic the metabolism of the biosphere.

That’s the message of McDonough and Braungart’s book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, which appeared two years after Expo 2000. Rather than a linear, cradle to grave/take-make-waste approach to production, we can design industrial processes to cycle nutrients the way nature does.

There is now a Cradle to Cradle (C2C) certification process developed by the Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute. A Registry of C2C certified products can be found there.

In their follow up book, The Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability-Designing for Abundance (2013), McDonough and Braungart go well beyond a “do no harm” / stewardship of the planet aspiration. Their vision for humans is positive, bold, and inspiring: “We should not just protect the planet from ourselves but should redesign our activity to improve the planet. And that goal is well within our reach.”

McDonough and Braungart are convinced that we can do this. What if instead of muddling along with the stale and dangerous mental model that waste is a thing, we all shared their mental model and vision of what is possible. From Cradle to Cradle:

“We see a world of abundance, not limits. In the midst of a great deal of talk about reducing the human ecological footprint we offer a different vision. What if humans designed products and systems that celebrate an abundance of human creativity, culture, and productivity? That are so intelligent and safe, our species leaves an ecological footprint to delight in, not lament?”

What if?