“We invade tropical forests and other wild landscapes, which harbor so many species of animals and plants—and within those creatures, so many unknown viruses. We cut the trees; we kill the animals or cage them and send them to markets. We disrupt ecosystems, and we shake viruses loose from their natural hosts. When that happens, they need a new host. Often, we are it.” ~David Quammen, author of Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Pandemic, in the New York Times January 28, 2020

Give Earth a Chance Button

The first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, was organized to call attention to and stop the same kinds of thinking and behaviors that led to the coronavirus pandemic.

For all the positive outcomes of Earth Day 1970 and subsequent Earth Days, as a society we still behave as if people are separate from and above the natural world, as if nature is an unlimited source of resources that are ours for the taking, as if taking those resources without regard for ecosystem functioning or the laws and limits of nature have no consequences, and as if nature is an infinite sink to absorb whatever and however much waste we produce.

Right now we are focused on what individuals, organizations, communities, and government should be doing to respond to this crisis – which is what we need to do – but at some point, we have to confront the fact: our worldviews and behaviors have caused every major global crisis we face including this one.

The most dangerous and wrong worldview of all is human separateness from the rest of the living planet.

The message in 1970 (and well before) is the message now: What we do to the natural world we do to ourselves. Everything is connected.

Early in the 20th Century, John Muir poetically observed: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” He intuited the interconnection and interdependence of everything.

Quantum physics subsequently proved Muir to be right. Physicist Fritjof Capra: “Ultimately, as quantum physics showed so dramatically, there are not parts at all. What we call a part is merely a pattern in an inseparable web of relationships.”

More than ten years ago, Peter Senge warned that the consequences of not understanding our interdependence are becoming ever more apparent and are growing exponentially as human population has exploded, as our impact on the planet has grown to be all-pervasive (thus the new geological epoch, the Anthropocene) and caused more and more harm, and as our economic, technological, and social systems have become increasingly interconnected. Unfortunately, Senge observed, our understanding of the interdependence of life has not grown very much. The coronavirus/COVID-19 crisis is one of the ways we are suffering as a result.

The first Earth Day was the brainchild of Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, a Wisconsin Democrat who felt that the environment needed political standing in Congress if the public interest was to be fairly represented. Senator Nelson recruited Republican Congressman Pete McCloskey from California to the cause, and hired Denis Hayes, a Harvard Law School student, to be the national coordinator.

Earth Day 1970 was the largest demonstration in American history. 20 million people participated. Well over a thousand colleges and universities held teach-ins and other events as did 10,000 K-12 schools.

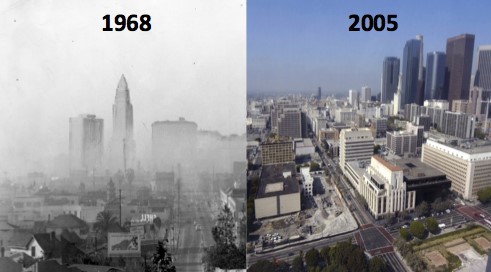

Several triggers representing broader issues lit the fuse of the Earth Day movement. Among them: The publication of Silent Spring in 1962, a devastating indictment of the profligate, irresponsible use of poisons like DDT to manage agricultural and neighborhood pests; in January 1969 the Santa Barbara drilling rig blowout and oil spill dumped 3 million gallons of crude into the waters of coastal California, the largest spill in history until the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989; the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland caught fire in June of 1969, as it had for decades. Air quality in cities like Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and Birmingham were every bit as bad as the air in Beijing today.

Air quality in Los Angeles. Photos: Herald-Examiner Collection, Gary Leonard

As surprising as it might seem today, Earth Day was a bipartisan event. The New York Times on April 23, 1970, reported: “Conservatives were for it. Liberals were for it. Democrats, Republicans, and Independents were for it. So were the ins, the outs, the Executive and Legislative branches of government.”

In the three years following Earth Day 1970, Congress passed the most consequential legislation ever to protect the natural world and public health: the Clean Air Act (which, in spite of anguished cries from industry, passed the Senate unanimously and the House by a voice vote), the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, and several other laws that have fundamentally altered life for the better. These photos are just two examples of the difference these laws have made:

Cuyahoga River, Cleveland, 1952. Photo: Cleveland State Univ. Library

Cuyahoga River, Cleveland, 2019. Photo: sharetheriver.com

The dramatic differences in these photos are explained by concentrated political action by citizens that forced government to act on behalf of the public interest. That forcing came when congressmen standing in the way lost their jobs.

Earth Day organizer Denis Hayes made this point in 2010 on the 40th anniversary of Earth Day while addressing climate change. “…winning passage of meaningful legislation on climate change requires more than slogans and green talk — it demands intense, determined political action…. Politicians who try to ignore climate disruption need to start losing their jobs next November.” Read Hayes’ entire post including a brief description of targeting a “Dirty Dozen” congressmen in 1970 (yes, they were all men) who stood in the way of environmental protections.

In the middle of the coronavirus crisis, we should pay close attention to how our elected representatives act to resolve this crisis, whose interests are being served, and what they do going forward to change the way things are done so that the next virus is less likely. Is the light dawning that we are interconnected and interdependent and must make fundamental changes to the way we behave toward each other and the natural world?

If not, as citizens who exercise the right to vote we have the opportunity – and the need – to create the same kind of change that citizens created in the early 1970s. The stakes are high.

As David Quammen put it in his January 2020 New York Times Opinion piece:

So when you’re done worrying about this outbreak, worry about the next one. Or do something about the current circumstances. Current circumstances include a perilous trade in wildlife for food, with supply chains stretching through Asia, Africa and to a lesser extent, the United States and elsewhere…. Current circumstances also include bureaucrats who lie and conceal bad news, and elected officials who brag to the crowd about cutting forests to create jobs in the timber industry and agriculture or about cutting budgets for public health and research. The distance from Wuhan or the Amazon to Paris, Toronto or Washington is short for some viruses, measured in hours, given how well they can ride within airplane passengers. And if you think funding pandemic preparedness is expensive, wait until you see the final cost of nCoV-2019.

We are faced with two mortal challenges, in the short term and the long term. Short term: We must do everything we can, with intelligence, calm and a full commitment of resources, to contain and extinguish this nCoV-2019 outbreak before it becomes, as it could, a devastating global pandemic (just three months later it’s too late for that now – ed.). Long term: We must remember when the dust settles, that nCoV-2019 was not a novel event or a misfortune that befell us. It was — it is — part of a pattern of choices that we humans are making.

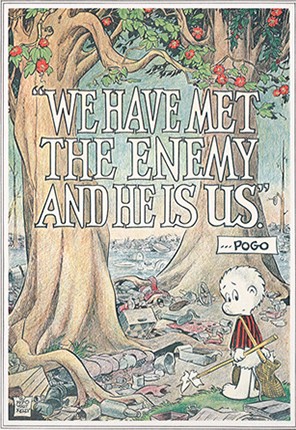

This is the same point Pogo made fifty years ago. This Pogo cartoon by Walt Kelly became an iconic image of the first Earth Day. It’s message? To paraphrase, ‘We have met the enemy, and the enemy is us.’

Seeing connections and acting accordingly. This is the most powerful lever we have to change the course of history for the better.

Very timely. Let us hope and pray we will be more prepared and better led through the next pandemic.

Thank you for this message that finds a connection in us for the past, present and future in all things.