Post contributed by Lisa A. W. Kensler, Emily R. and Gerald S. Leischuck Endowed Associate Professor for Educational Leadership; Department of Educational Foundations, Leadership, and Technology in the College of Education

We are all systems thinkers. We all have the capacity to see beyond the obvious, to look deeply, to explore otherwise hidden connections. As young children, we were masters at this work. We learned early on how to influence and even manipulate our earliest social system, our family, in order to meet our needs and wants. We learned that our facial and vocal expressions would elicit different responses from our parents, siblings, and caregivers. As our physical abilities expanded, we learned how to navigate the natural world with greater ease – walking, running, climbing, and playing. We asked questions with limitless curiosity. Before too long, we entered school where knowing the ‘right answers’ became more important that our spirited inquiry and creativity. For many of us, our capacity for systems thinking atrophied. All this while our world became more deeply interconnected and interdependent, our local and global challenges increased in complexity and systems thinking emerged as more critical than ever.

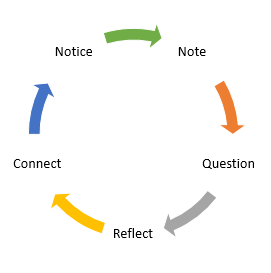

Like any atrophied muscle, reawakening our capacity for systems thinking takes some time, exercise, and practice. Before sharing a few suggestions for strengthening your systems thinking fitness, let us take a moment to define our terms. Systems thinking is thinking about systems. Systems include everything from molecules and smaller to our biosphere and beyond. Dynamic systems are continuously changing, so tracking patterns over time is crucial if we truly want to understand these systems. Systems are nested within systems, adding to their complexity. A major challenge for systems thinkers is knowing when to narrow the boundary of a system under consideration and when to broaden it. What about thinking? We all know what thinking is, right? We may have thoughts non-stop, but we are not necessarily thinking non-stop. Thinking involves noticing what we notice, noting our ‘noticings’ (what we notice), questioning what we notice, reflecting on our questions and emerging answers, and making connections to old and new noticings. This type of thinking is exploratory, intentional, and demanding. Donella Meadows noted,

Like any atrophied muscle, reawakening our capacity for systems thinking takes some time, exercise, and practice. Before sharing a few suggestions for strengthening your systems thinking fitness, let us take a moment to define our terms. Systems thinking is thinking about systems. Systems include everything from molecules and smaller to our biosphere and beyond. Dynamic systems are continuously changing, so tracking patterns over time is crucial if we truly want to understand these systems. Systems are nested within systems, adding to their complexity. A major challenge for systems thinkers is knowing when to narrow the boundary of a system under consideration and when to broaden it. What about thinking? We all know what thinking is, right? We may have thoughts non-stop, but we are not necessarily thinking non-stop. Thinking involves noticing what we notice, noting our ‘noticings’ (what we notice), questioning what we notice, reflecting on our questions and emerging answers, and making connections to old and new noticings. This type of thinking is exploratory, intentional, and demanding. Donella Meadows noted,

“Living successfully in a world of systems requires more of us than our ability to calculate. It requires our full humanity – our rationality, our ability to sort out truth from falsehood, our intuition, our compassion, our vision, and our morality.” (Meadows, 2008, p. 170)

If your capacity for systems thinking has atrophied over the years, here are a few suggestions for cultivating this skill set. These suggestions follow the iceberg model, a systems thinking tool featured in many systems thinking resources including the book, The Fifth Discipline, and The Waters Foundation’s website.

Notice what you notice. What is attracting your attention? Why? What is worth your time and effort for further exploration?

Notice what you notice. What is attracting your attention? Why? What is worth your time and effort for further exploration?- As you focus in on an area of interest, what system boundaries are you drawing? In other words, what are you focusing on and why? Are there nested systems within this system, or is this system nested within other systems that also need your attention?

- Now that you have established some boundaries, what patterns and trends have been occurring in this system over time? How far back do you need to look? Why? Are there less obvious patterns and trends that may be important for understanding the system and its behavior over time?

- As you consider a variety of factors related to the system under consideration, can you begin exploring causal relationships among these factors that might explain the patterns and trends? The key here is finding the sources of feedback in the system. What is reinforcing the system’s behavior? What is balancing the system’s behavior?

- Do you wish to change the system’s behavior in some way? If so, there is leverage for change embedded in the causal relationships you just identified. What opportunities do you see for influencing the system? Take some action and watch how the system responds… notice what you notice!

Systems thinking applies to all areas of our lives. Systems thinking tools help guide and structure our thinking such that we are likely to notice more, ask more interesting questions, and find more diverse and meaningful connections – all leading to improved learning, leadership, and action.

I’d like to offer another real-life example from a colleague of mine, her client commented (at the event level): “People weren’t talking and the meetings weren’t functional. Our work is creative, about emotion and passion, but people were detached; I was flummoxed as to why people weren’t contributing.”

The shift (at the mental model level) came from a systems game using the Iceberg model to expose hidden dynamics around the power structures underpinning the ideas process, rather than more tactical information like product goals.

As you say, systems (specifically, organisational systems) are complex and people gain significant insight by stepping back and taking a holistic look at the system.